Longlegs 2024

It all begins with a flashback, framed similarly to a home movie; letterboxed format, rounded corners. A car pulls up to a pearly white home in rural Oregon, attracting the attention of a young girl. Without fear, she puts on her winter-coat and goes to take a look, stopping at about the halfway point between the vehicle and her home. The ensuing encounter proves pivotal, and sets the tone for Osgood Perkins’ Longlegs, an unbridled masterpiece.

Fast-forward a few years and we’re in the 1990s (although it doesn’t quite feel like it — more on that later). FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) is assigned her first case. Acting on something of a psychic hunch, she captures a serial killer, leading her superiors to believe she might not be just another faceless agent capable of adhering to commands. Following a series of personality tests, Lee is assigned the mysterious case of the Longlegs serial killer.

Over the span of three decades, a few dozen murders have been committed, all with striking parallels: a churchgoing father abruptly goes off the deep-end and slaughters his wife and young children in brutal fashion before taking his own life. There is never any forensic evidence from anyone outside of the home at the scenes of the crime. The connective tissue is simply the presence of a sweet birthday card with a coded message written on it, signed “Longlegs.”

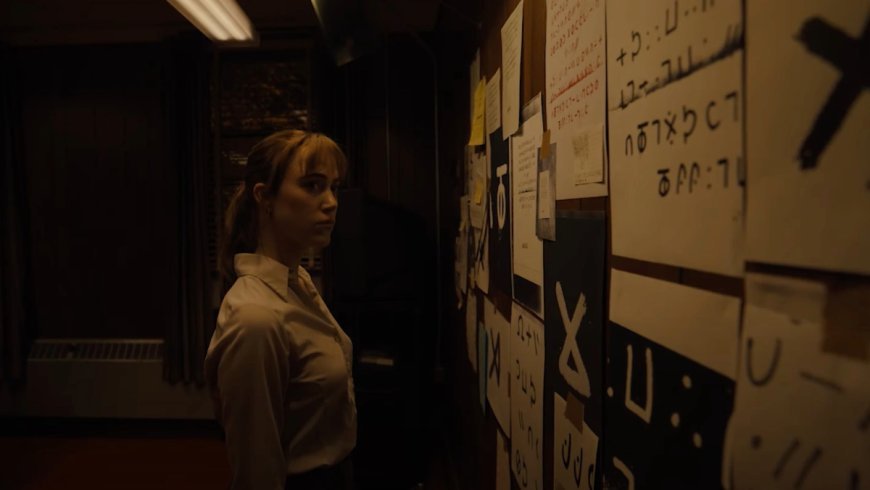

Lee joins Agent Carter (Blair Underwood) on the case, using her seemingly infinite brain-power and meticulous attention-to-detail to crack many of Longlegs’ codes. She’s forced to grapple with a past she cannot easily recall. Lee was raised by her mother, Ruth (Alicia Witt), an ultra-religious hoarder who phones frequently, asking her daughter more than a few times if she’s said her prayers.

And then there’s Longlegs himself. Played by Nicolas Cage in a chameleon-like performance, he’s the personification of evil, a loyal follower of Satan with painted white skin (similar to a clown not fully made-up) and dusty gray hair. In an era where ostensibly every film needs three or four trailers, a surplus of posters and stills, and the first ten minutes released before it even hits theaters, the marketing team at Neon have done an exceptional job at hiding Cage’s character from the world.

One of many beautiful things about Osgood Perkins’ latest film is how it plays like a nightmare. There are frequent flash-cuts to brief interludes which feature any/everything from crime-scene photos, blood swirling into an optical illusion, to a close-up of a snake’s body bathed in a red hue. The majority of the picture might be set in the 1990s (Bill Clinton’s presidential portrait hangs above Agent Carter’s desk), but the aesthetic suggests mid-to-late 1970s, further loaning itself to that of a hybridized dream.

Perkins also makes no bones about who Longlegs is, though he’s careful not to reveal his face until relatively late in the film. Even when he’s revealed, the very sight of him makes us uneasy. He’s the scariest new movie character I can remember: unpredictable, cunning, cryptic, and maniacal. You can’t take your eyes off of him, and you might feel the hairs on the back of your neck rise when Lee finally gets her long-awaited face-to-face with the man behind these atrocities.

But then again, how is Longlegs involved when there is no forensic evidence incriminating him of these seemingly random domestic murders? Even while orchestrating a living nightmare of a movie, brimful with tension, artistic craft, and dread, he still thoughtfully details a gripping crime procedural we uncover through the eyes of Lee. Maika Monroe — an underrated modern “scream queen,” with career highlights including It Follows and The Guest — and her expertly articulated nervous energy do their part to bleed over to the audience. Lee is perpetually uncomfortable, so choked by the fear of what she doesn’t know and the anxiety bred from what she’s uncovered, that we as viewers start to feel the same. It doesn’t help when Cage, who perhaps hasn’t been this much of a loose cannon since Vampire’s Kiss, might be waiting in the next scene to terrify us with whatever he happens to do next.

Perkins frames the hell out of Longlegs, making tremendous use of negative space by sometimes placing the camera in the corner of the room as it voyeuristically watches someone populate it. Cinematographer Andrés Arochi assists by favoring medium-length, static shots that frequently jostle our perspectives. Zilgi’s score is hair-raising as well, which might seem like a challenge when the film has an epigraph from T. Rex’s song “Bang a Gong (Get it On)” and closes with the very tune.

Longlegs slithers under your skin in a masterful way, thanks to a wide variety of elements all coalescing into one of the finest horror films of this, or any other year. Some might lament that Perkins leaves a few threads hanging by the time the closing credits (which crawl down the screen, rather than up). I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have a couple small misgivings. But when a film is so expertly aware of the mood it seeks to create, and delivers a disquieting examination of something that is equal parts unstoppable and unknowing, with this much craftsmanship and talent on display, I can be forgiving. It’s been too long since we’ve seen an amalgam of the psychological and supernatural to this effect, which in itself is further proof just how rare Osgood Perkins is as a filmmaker.